The Human Rhythm: Why the Golden Section Matters

When we discuss the Golden Section in the human body, we must tread carefully. The human form does not—and should not—conform perfectly to a mathematical ideal. You only need to spend an afternoon at the beach to see the truth: bodies are beautifully varied, asymmetrical, and shaped by the messy realities of genetics, culture, and age. Yet, despite this diversity, proportional relationships mirroring the Golden Section appear again and again—not as rigid rules, but as persistent tendencies.

The Artist’s Intuition

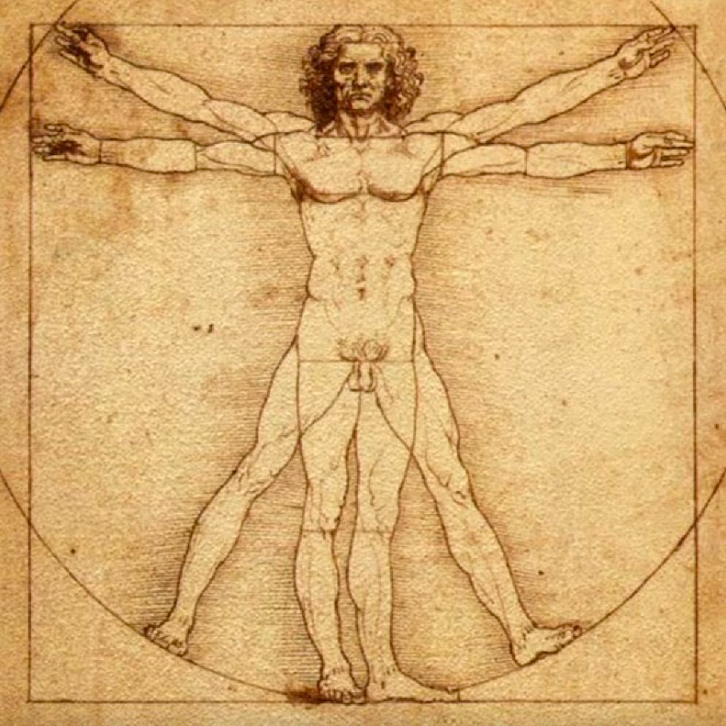

Artists noticed this long before scientists attempted to quantify it. Classical sculptors and Renaissance painters studied the body obsessively, searching for proportions that felt balanced rather than merely "correct." Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man is less a diagram of perfection and more an exploration of relationship—how the body organizes itself around a center. From the ratio of the navel to total height to the spacing of facial features, many of these measurements hover near that familiar 62%–38% division.

Beyond Beauty: The Logic of Stability

Why does this matter? Because humans are hard-wired to read bodies. Long before we think consciously, we register whether a form looks physically coherent—whether it could plausibly stand, move, or bear its own weight.

This isn't about "attractiveness" in a commercial sense; it’s about intelligibility. When the relative sizes of the head, torso, and limbs fall within these familiar ranges, the figure reads as stable and alive. When these relationships are absent, the body feels awkward or weightless, even if the viewer can’t quite pinpoint why. A body with natural proportion makes visual sense because it appears governed by gravity and anatomy. We believe it could walk, reach, or turn without collapsing. That belief is what creates "presence."

The Anchor of the Figure

The Golden Ratio approximates how mass is distributed around our center of gravity. When artists use these proportions—even loosely—the figure feels anchored in space. This explains why even highly stylized figures can feel convincing; they may exaggerate or simplify, but as long as they preserve these key proportional rhythms, the body still "adds up." The viewer doesn’t admire the math, but they trust the figure.

This logic extends into movement. Walking, reaching, and bending all involve proportional relationships that minimize strain and maximize efficiency. Over time, these mechanical efficiencies shape our form. In the human body, what looksbalanced often is balanced.

Recognizing the Rhythm

For the artist, the Golden Section is not a formula to be imposed, but an underlying rhythm to be recognized. It provides a shorthand for placement, scale, and emphasis—helping us decide where the weight should rest and where a gesture should resolve.

In the end, these proportions remind us that we are not separate from the patterns we admire in the world around us. The ratios we find beautiful in art and nature are written, imperfectly but unmistakably, into ourselves.